Energizing and Draining

2024.07.04.

This morning, I was walking in the forest with my dog, Ottó. We’ve already lost two balls, so today I brought him a ring to play with. I was terrible at it—it turns out you need to throw it very differently than a stick or a ball. In my clumsiness, I either threw it off to the side or dropped it right in front of me. If there was a way to mess it up, I found it. While I was brooding over my own ineptitude, I noticed how happy Ottó was. He was running back and forth, bringing the ring back and then immediately rushing off again. He was smiling. Even after almost an hour, despite the heat, even in the forest, he was still happy. I didn’t bring any water. His tongue was hanging out, but he just kept running, wagging his tail, and his eyes sparkled.

Could he be happy?

Even with the poor throws, the heat, the thirst, the dust? How does he do it? How can he be happy despite all these things? We humans have been pondering the question of how to be happy for a long time. Hundreds of literary works explore this question, philosophers write dissertations about it, psychologists explain its psychological background, and life-coaching motivational seminars offer instant solutions with special discounts.

Ottó hasn’t seen or read any of these. I haven’t taught him anything about it either. I taught him to sit, lie down, march, and stay, but not how to be happy. So how does he know how? And why don’t we, if we’re supposedly further along in evolution? Could it be that happiness doesn’t offer an evolutionary advantage? Could the pursuit of happiness, which so many see as the goal of life, be something we lose in the process of evolution because it’s disadvantageous from an evolutionary perspective? If we were happy, would we lose our motivation to evolve? Would we stop developing new theories, techniques, and tools to reach this much-desired goal of happiness?

Ottó is happy.

And it seems like he’s evolving too. So, what does he know that he can do it and we can’t? Even though he can be so silly at times. The ball is right in front of him, and he can’t find it. He sniffs around, spins, runs, and doesn’t see it. How can he and his breed be trackers if they can’t even find a bright red rubber ball right in front of them?! Does it bother him? Well, when he finally finds it, he brings it to me, jumping with childlike joy. So, I don’t think he spends much time pondering it.

He just is.

And when do I have moments like that? When do I not think, but just be and enjoy? For example, during sex. That’s when I’m definitely not thinking about why something feels good. My anatomical and biochemical knowledge from university doesn’t run through my mind like, “AHA, this feels good because my neurotransmitters are...” I think that would be the end of the fun. We humans can experience something as simply good, without dissecting it.

Does thinking take away our ability to be happy? Or is it that we find it difficult to be happy and think about it at the same time? Do you ever think about how to be happy when you’re actually happy? I don’t think so. We think about it when we’re not happy and want to know how we can be. If we understand it, we can control it. We can do something about it. The desire to understand is embedded in our existence.

So, I want to be happy. To be happy, I need to understand what happiness is, how it compares to where I am now, and then I just need to figure out how to get from A to B.

But what is happiness?

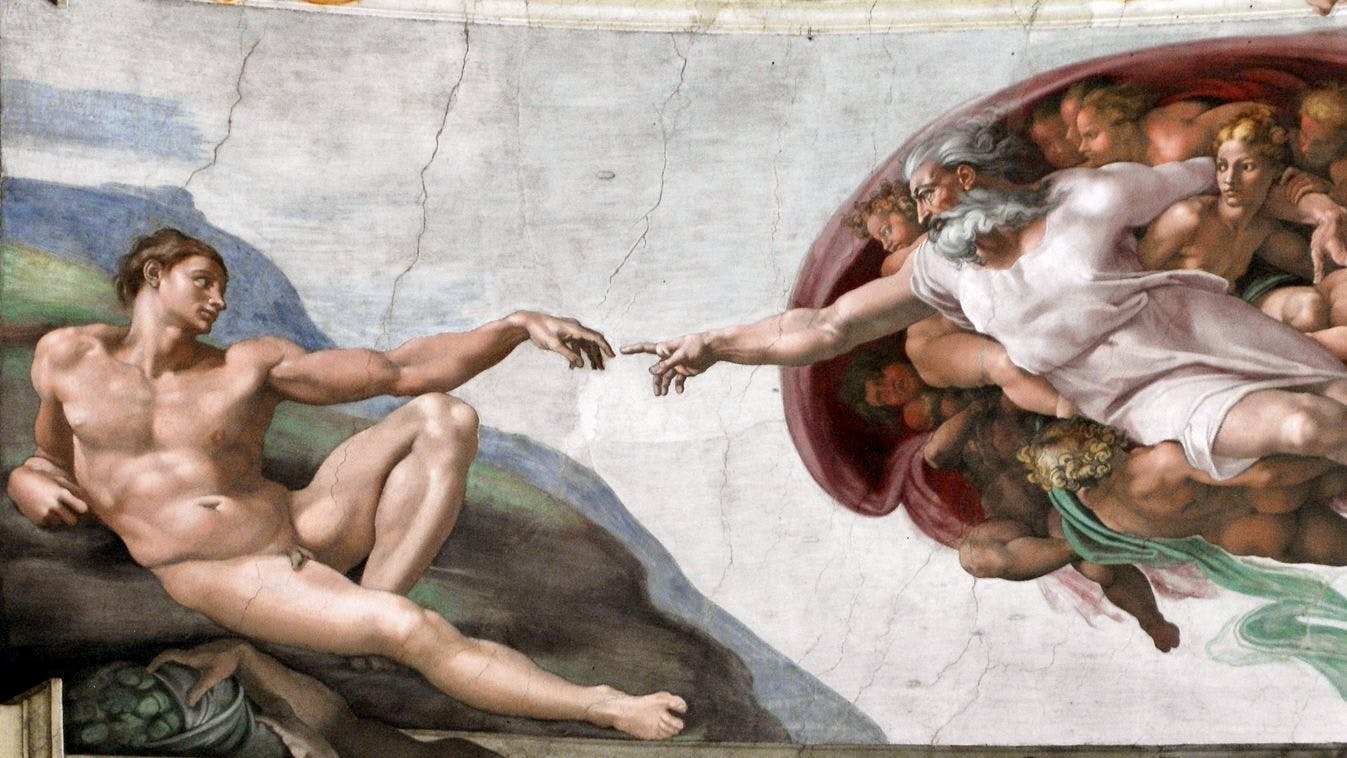

I’ve read, learned, and heard so much about it. Maybe it’s something like what the ancient Greeks said, that happiness is a full life, well-being, and living virtuously? Or perhaps it’s the state of ultimate liberation, free from suffering and desire? Or the inner happiness and divine joy that comes from spiritual enlightenment? Or perhaps it’s the American dream, the combination of material wealth, success, and personal freedom? Or “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven”? “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted”?

Ottó is happy.

And I don’t think he’s worrying about which category he falls into. He just is. Maybe it’s because he strives to do things he enjoys and avoids doing things he doesn’t. And when he does something he doesn’t like, he doesn’t try to convince himself that it’s good or will be good if he does it. He just tries not to do it. And it’s not a problem if it’s hot, as long as he enjoys the game, he’ll chase after the ball, stick, and ring. Even if I only manage to throw it five meters or if I throw it out of sight. But when he doesn’t want to anymore, he stops. He’ll lie down by the path, chew on a stick, and wait. Of course, if it’s for my sake, he’ll get up and do it again.

And he’ll still be happy.

Is that what we should do too? Strip down the complex methods of happiness to just focusing on one thing? On what’s good and what’s not?

What’s good? Well, it’s what energizes you, what makes your body tingle even when you’re utterly exhausted. And what’s bad? Perhaps it’s what drains the life out of you even when you’re full of energy. Isn’t it normal to strive for more and more situations in our lives that energize us and fewer that drain us? And I know, I know: life has situations we don’t choose, that fate, or someone we call fate, imposes on us. Sometimes things are tough, difficult.

But the effort to have more of what energizes us and less of what drains us, day by day, can already give us the feeling of happiness. The sense that day by day, things are getting better. That we’re moving closer to ourselves.

And that’s growth.

And maybe that’s all happiness is—the feeling that sometimes, we’re close to ourselves.

--

The article was translated from Hungarian to English by ChatGPT. Thank you, ChatGPT, for being here.